In the preface to her book

Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life, Yashodhara Dalmia says it is her aim to show, through close attention to Sher-Gil's life, "how genius is not born but made, indeed self-made". This is an admirable way of approaching the life of an artist, and Amrita Sher-Gil contains a great many rich and beautiful passages that show us how Sher-Gil, rapt in her own talent and hungry for a way forward, turned talent into genius by learning from both art and life.

Sher-Gil (1913-41) was a woman well in advance of her time. Half-Indian and half-Hungarian, of aristocratic lineage, she was born in Budapest and brought up in the Hungarian capital and in Shimla. She studied art in Paris in the wake of high modernism - unusually, her family relocated to Paris just so that she could make good on her talent - and reached a level of considerable technical accomplishment while still in her teens.

Her youthful work, already highly proficient, blossomed out in several directions upon her return to India for good in 1934 at the age of 21. Travelling around the country and taking inspiration from indigenous traditions - the frescoes at Ajanta and other sites in south India, Mughal miniatures, paintings of the Basohli school - she produced through her twenties works of haunting beauty and striking, if not always successful, technical innovation. Sher-Gil's life was just as vivid: she had many lovers, friends and enemies, married her first cousin, and died tragically young at the age of 28, possibly as the result of a failed abortion.

Although her work was very varied, Sher-Gil's women are of special interest. Dalmia quotes an entry from Sher-Gil's diary when she was just twelve, about a child bride, noting the pathos of the little girl sitting silently in a corner, a "helpless toy" in the hands of those responsible for her well-being. The women of Sher-Gil's paintings are grave, although they often seem tremulous with suppressed feeling. One of her earliest successes, made during her Paris years, was

The Professional Model (1933). The woman is ostensibly independent, but her slouched posture, sagging breasts hanging over a pouchy stomach, and plaintive eyes show that she too is helpless and pathetic in her own way - she does not even bother to strike a pose.

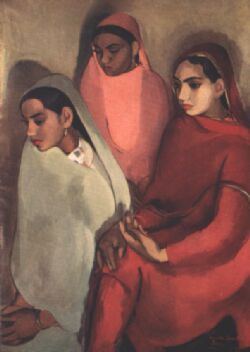

Two years later, after her return to India, Sher-Gil made

Group of Three Girls (at right) - t

he girls very

still from foreground to background, their eyes lowered or averted, each lost in thought, a group and yet not a group, the light sober and low, the heavy colours of the clothes, the scene giving off a gloominess, a sense of something cramped and silent. Her two major works -

Bride's Toilet and

Brahmacharis, both made in 1937 - also convey this air of quiescence and melancholy. Like many artists, Sher-Gil appears to have found images of Indian life constricted by poverty and oppressive social strictures morally disturbing but aesthetically striking. In her early years in India she writes often of wanting to paint "those images of infinite submission and patience".

"Those images of infinite submission and patience" - three decades later, another young artist with roots in India would arrive in the country of his

forebears, and be struck at once by just this aspect of the country. This is VS Naipaul on page two of

An Area of Darkness (1964), describing how he is received aboard ship at Bombay by the Goan guide Coelho. Naipaul and Coelho speak roughly as equals, but there soon appears a third presence - "Coelho's man" - who appears to be a denizen of a different universe:

[Coelho] clapped his hands and at once a barefooted man, stunted and bony, appeared and began to take our suitcases away. He had been waiting, unseen, unheard, ever since Coelho came aboard. Carrying only the doll and the bag containing the bottles, we climbed down into the launch. Coelho's man stowed away the suitcases. Then he squatted on the floor, as though to squeeze himself into the smallest possible space, as though to apologize for his presence, even at the exposed stern, in the launch in which his master was travelling.

The best thing about

Amrita Sher-Gil is that Sher-Gil is not just spoken about on these pages; she also does a lot of speaking herself (and therefore seems not dead, and memorialized, but still alive and thriving, as she is in one sense). Sher-Gil shared a lively correspondence with several people, including her lover and eventual husband Victor Egan and the Bombay-based art critic Karl Khandalavala, who was a great champion of her work and wrote a book about her shortly after her death. Dalmia quotes liberally from her correspondence, showing what an adept interpreter she was not just of Gauguin (whom she admired greatly), Basohli paintings or the Ajanta frescoes but also of her own work, both the intent with which she began and the actual strengths and weaknesses of the result. In fact, she was not shy of speaking her mind on any subject. Here she is in a talk delivered at Lahore in 1937, castigating Indian film-makers for presenting in their work only the make-believe world of the studio:

When the people who are responsible for the production of films in this country discover the rich beauty of a blade of corn, the rough unctuous texture of the earth, the rhythm of movement found in massive bullock drawing ploughs…and learn to discard the synthetic substitute of the studio they will do great things. […] I would like them to notice the undulating lines in South Indian sarees and the beauty of the thin peasants in their strange straight dhoties, to notice the glossy beauty of the rice fields and the shimmer of dust rising in the sun, to focus their lens on small objects and invest them with a charm and a significance that surpasses all pomp and tinsel of the ancient courts or Indra's heaven.

This paean to natural beauty has an almost direct echo in a lyrical passage from "My Life, My Work", a lecture delivered by Satyajit Ray in 1982, in which he describes (in Gopa Majumdar's translation) how he made the move out from the controlled conditions of studio shooting and attempted to grapple with the problems of capturing sights and sounds on location:

If the books on film-making helped, it was only in a general sort of way. For instance, none of them tells you how to handle an actor who has never faced the camera before. You had to devise your own method. You had to find out by yourself how to catch the hushed stillness of dusk in a Bengali village, when the wind drops and turns the ponds into sheets of glass, dappled by he leaves of shaluk and shapla, and the smoke from ovens settles in wispy trails over the landscape, and the plaintive blows on conch shells from homes far and near are joined by the chorus of crickets, which rises as the night falls, until all one sees are the stars in the sky, and the stars that blink and swirl in the thickets.

In a letter written in 1931 Sher-Gil declares: "I will enjoy my beauty because it is given for a short time and joy is a short-lived thing." She was not to know that life itself was given to her "for a short time". But the colour and pitch of that short, incandescent span of years emerges vividly in

Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life. The logical sequel to this book would be for Dalmia to now bring out a collection of Sher-Gil's radiant letters and essays.

Sher-Gil's painting

Village Scene recently sold for Rs. 6.9 crore at an auction in New Delhi. Here is Dalmia's piece on

that event, and here is

an essay by Karl Khandalavala on Sher-Gil's work. Several Sher-Gil paintings are part of the collection of the

National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi.

And here are some more exceptional essays on artworks and artists: the great art critic Robert Hughes

on Rembrandt, Sebastian Smee again

on Rembrandt (it was Rembrandt's 400th birth anniversary recently, and discussion of his famous self-portraits also appears in Dalmia's book), Rochelle Gurstein on

the Mona Lisa, and John Updike

on Goya. And lastly this fun essay by Jacob Weisberg:

"Matisse vs. Picasso: You're Either One of the Other", and an essay by Pankaj Mishra on Naipaul's

An Area of Darkness.