This essay appears in my recent book My Country Is Literature

But what is so noteworthy about the novel as a lens on history? It might be argued that even as a form of story, let alone history, the novel does not enjoy great currency in India, for it is neither an indigenous form nor a mass one. Cinema has far greater mass appeal, and the stories and narrative conventions of epics like the Ramayana inform everyday life and moral reasoning much more than any novel does (notwithstanding the apparent desire of nearly every educated Indian to write a novel, ideally bestselling).

Yet if the novel deserves to be studied as a site of Indian history, it is because Indian history itself is one of the great subjects of the novel in India. A preoccupation with Indian history—its pleasures and possibilities, its continuities and its fractures, its burdens and its freedoms, its shape and its mysteries—is a thread running through the work of some of the greatest Indian novelists of the past century and more, across more than two dozen Indian languages and literary traditions. In the great diversity of narrative forms and interpretative cruxes generated by the Indian novel, there lies, waiting to be unpacked by the active reader, a wealth of wisdom about Indian history—and therefore about how to live in the present time as an Indian and a South Asian, as a modern person of the 21st century and as a citizen of the first century of Indian of democracy. (Some of these possibilities are apprehended or activated by characters in novels themselves, allowing us to experience vicariously, or in advance of actual historical fact, difficult dilemmas and choices in our own lives.)

Consider Fakir Mohan Senapati’s enormously sly, satirical and lightfooted novel Six Acres and a Third (1902). The plot of Senapati’s novel revolves around a village landowner’s plot to take over the small landholding of some humble weavers. But this is also the Indian village in the high noon of colonialism, and the first readers of Senapati’s story would have delighted in the many potshots taken by the narrator against new and perplexing British institutions or perverse intellectual fashions, administered and advanced by a new class of English-educated Indians. ‘Ask a new babu his grandfather’s father’s name, and he will hem and haw,’ the narrator chirps, ‘but the names of the ancestors of England’s Charles the Third will readily roll off his tongue.’

The story appears to be generating, then, an argument about history and about political resistance. India must rid itself of its colonial masters, it seems to say, because they have delegitimised many of the traditional knowledge systems and truths of Indian society, and in the process made the modern Indian self-imitative and inauthentic. (The argument persists in today’s debates about ‘westernisation.’)

But this raises a new question, one that is not lost on Senapati. Was traditional Indian village society itself ever very wise, just, or balanced? As the story progresses, we see that anti-colonial sentiments have not blinded the narrator to the need to subject his own side to the scrutiny of satire. When we hear that ‘The priest was very highly regarded in the village, particularly by the women,’ and that ‘The goddess frequently appeared to him in his dreams and talked to him about everything’ the complacency and mystifications of Brahmanical Hinduism are also laid bare, as is the credulity about those who would place their faith in such a system.

Senapati’s irony is particularly effective because of its double-sidedness, and leads to a point useful as much in our time as his own. That is: criticism of a clearly marked-out ‘other’ (to Indians in the early 20th century, the British; to Hindu nationalists today, Muslims and Christians) often legitimises a sweeping and complacent faith in one’s own worldview; that the search for truth or meaning in history must remain a charade if not accompanied by the capacity for self-criticism. The novel’s argument, buried in its details and never overtly stated, is liberating not because it is comforting or inspiring, but precisely because it is disenchanted. Fiction shows us how human beings are themselves fiction-making creatures, and must therefore take special care to scrutinise what they believe to be foundational truths.

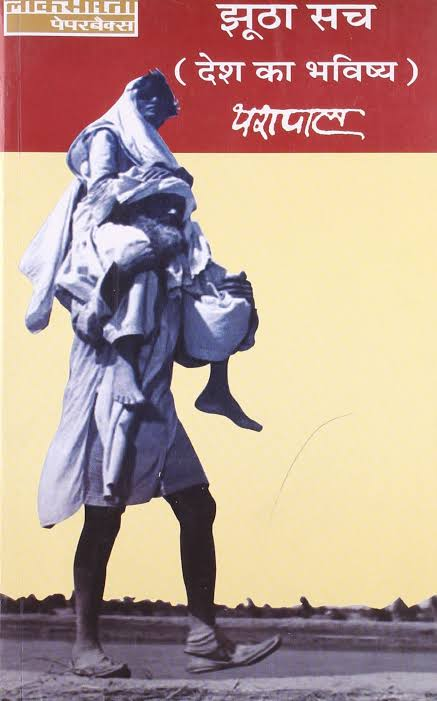

A different kind of novelistic irony—cosmic rather than comic—radiates from This Is Not That Dawn, the English translation of Jhootha Sach, the Hindi novelist Yashpal’s thousand-page novel from the 1950s about Partition. The story tracks the lives and loves of Tara and Jaidev, a pair of siblings, across the worlds of Lahore and New Delhi in the years both before and after Partition. In so doing, Yashpal’s novel generates dozens of alternative views of that cataclysm from viewpoints male and female, Hindu and Muslim, Indian and Pakistani (at the very moment that these new highly charged and adversarial identities are coming into being), prospective and retrospective.

Each character’s position or dilemma carries its own distinctive charge of hope, memory, conviction, doubt, naïveté, prejudice, fatalism, cynicism: a vast narrative collage of human beings swimming valiantly with and against the tides of history. If the narrator himself has something to say about the logic or validity of the breaking up of India, it remains parcelled out among the characters, and must be intuited by the reader.

In fact, although the book faces up squarely to the tremendous violence and horror of Partition, the feeling we take away from Yashpal’s novel is not that of an entirely tragic story. Of course, Partition destroyed a particular shared and longstanding, if uncodified, sense of what it meant to be Indian. But as we perceive from the quest of the protagonist, Jaidev Puri, to start his own newspaper rooted firmly in a rejection of religious partisanship of either a Hindu or Muslim stripe, what it means to be Indian would, in a new democratic and secular republic, have entailed building upon a new foundation in any case. At certain junctures in history, the novel shows us, tragedy and moral progress may be inseparably mingled.

As we can now see more than seven decades later, the new Indian republic has faced many challenges in remaining secular (and indeed democratic). Perhaps, in retrospect, we might say that it asked too much of the first citizens of independent India, who might have preferred political independence while remaining wedded to their old ways of social organisation. A splendid insight into the tensions between the hierarchical imperatives of Hinduism and the egalitarian impulses of the new Indian democracy might be found in the novels of the great Kannada novelist UR Ananthamurthy, and nowhere more convincingly so than in his early novel Samskara (1965), published when Ananthamurthy was just 33.

Samskara is, as the title indicates, about rites for the dead. Its plot turns on the dilemma posed by Naranappa, a man even more troublesome dead than alive. Naranappa is a member of a small agrahara, or settlement, of brahmins in rural Karnataka. The brahmins are, for the most part, almost stereotypically true to type: they live off alms and donations, perform rituals for the rest of the community, interpret the sacred books, and uphold through both poetry and penance the values of an ancient (and apparently eternal) hierarchical social order.

But Naranappa has gone rogue, profaning the tradition, provoking his neighbours with orgies of drinking and meat-eating, living in sin with a woman of a lower caste. There is no taboo he has not traduced. If he has not been excommunicated, it is only because the agrahara’s leader, the wise and compassionate scholar Praneshacharya, has long waged a war to reform his demoniacal nature. When Naranappa suddenly passes away, a question of profound significance comes up, one on which the entire world order seems to turn. Must the dead man be cremated with all the respect due to a high-born Brahmin? Or will the brahmins who survive him themselves be polluted by performing the last rites of someone who devoted himself to ‘kicking away at brahmanism’? It is Praneshacharya who must decide. Confused, the man widely known as ‘the Crest-Jewel of Vedic Learning’ turns to his palm-leaf manuscripts for guidance. What precedents exist for a conundrum such as this?

Upon the horns of this beautifully counterbalanced conflict—dead against the living, hedonism against self-restraint, profaner against pardoner, sexuality against textuality—Ananthamurthy sets down an allegory of Indian history with a particular resonance for the 20th century, and indeed the one after. For although the novel appears to be set in the unchanging Village Time of old India, in actual calendar time we are somewhere in the 1950s, in the levelled world of the new Indian democracy, that has made its touchstone not the books of revelation, but a constitution thrashed out by human beings.

Slowly, our view of the dead man’s misdemeanours changes colour. Perhaps Naranappa, underneath the obvious provocation of his saturnalia, represents the spirit of the new freedom, blowing away the fossilised thinking sanctified by the centuries. In openly falling in love and living with a low-caste woman, Naranappa shows a greater humanity than that required merely by ‘keeping the faith.’ Unlike his compatriots, flapping cantankerously in manacles of jealousy and moralism, he thinks on his feet and with his body.

Even the spotless Praneshacharya finds himself morally discombobulated by the age: his righteousness is founded upon a deep social conservatism, and he thinks through the foundational categories of purity and pollution, which find no place in the new social compact. The brahmins, we see, are prisoners of history, huddled in a cocoon of hypocritical piety; never daring to live beyond the ‘duties a brahmin is born to.’ Teaching all other castes to keep their own boundaries, they preside over a sterile society, when the age demands a new moral creativity. When they face a dilemma, they delve into their palm-leaf manuscripts, not into themselves. Praneshacharya begins to perceive this, but is powerless to act upon his intuition. Until his body does. On a trip deep into the forest to seek out an answer at the feet of a god, he encounters Naranappa’s voluptuous companion and ends up sleeping with her.

Now Praneshacharya, too, is a sinner, forced to confront his own repressed carnality. ‘I suddenly turned in the dark of the forest,’ he ruminates. Smarting with shame but rapt with a strange exhilaration, he takes to the road, both running away from himself and in search of himself. Ananthamurthy’s finespun prose, rendered in exquisite cadences by his late translator AK Ramanujan, tracks with great rigor the inner monologue of Praneshacharya as he arrives a new vision of the self. And as we follow Praneshacharya there, we see that we have reached a point not just metaphysical but metafictional. In place of the Sacred Books, perhaps it is the novel that contains the wisdom and the doubt that India needs for a new age in its history (which would make Ananthamurthy a kind of novelistic Naranappa). It’s a startling story, one as provocative for its time and place as those of Cervantes, Sterne and Diderot must have been in theirs.

As these examples show, the work of novels is not confined to mere representation of historical realities (although this is where they may start). Rather, a novel may be a creative intervention in history in its own right—an actual agent of history, passing on to the reader who passes through its narrative field both its diagnostic powers and visionary charge. Indeed, from Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay to UR Ananthamurthy, Bankimchandra Chatterjee to Kiran Nagarkar, Qurratulain Hyder to Salma, Phanishwarnath Renu to Amitav Ghosh, novelists have generated some of the most layered and sophisticated visions of Indian history produced in the last two centuries. Yet as a group they fall into no school or political camp—some of them possess a conservative rather than progressive sensibility. What unites them is their interpretative power and their ability to illuminate and complicate the particular historical crux they focus on.

It would appear that there is something inherent in the novel form—the persuasive power and freedom of a story when compared to a discursive argument; the prospect of linking the world of the self with that of the community and society; the freedom to rove in spaces of the past that we cannot access by means other than that of the imagination; the potential to think dialectically in exchanges between characters or switches in perspective between the narrator and the characters—that makes the space of the novel a particularly fertile ground for historical thinking.

And when they are themselves reinserted into the canvas of Indian history, it seems to me that the projects of the Indian novel and that of Indian democracy (both fairly new forms in Indian history) appear uncannily similar—and perhaps similarly unfinished. As Indian democracy has over the last seven decades sought to fashion a new social contract in a deeply hierarchical civilisation, so the great Indian novel has attempted not just to address but also to form a new kind of reader/citizen, alive to both the iniquities and the redemptive potential of Indian history.

But Naranappa has gone rogue, profaning the tradition, provoking his neighbours with orgies of drinking and meat-eating, living in sin with a woman of a lower caste. There is no taboo he has not traduced. If he has not been excommunicated, it is only because the agrahara’s leader, the wise and compassionate scholar Praneshacharya, has long waged a war to reform his demoniacal nature. When Naranappa suddenly passes away, a question of profound significance comes up, one on which the entire world order seems to turn. Must the dead man be cremated with all the respect due to a high-born Brahmin? Or will the brahmins who survive him themselves be polluted by performing the last rites of someone who devoted himself to ‘kicking away at brahmanism’? It is Praneshacharya who must decide. Confused, the man widely known as ‘the Crest-Jewel of Vedic Learning’ turns to his palm-leaf manuscripts for guidance. What precedents exist for a conundrum such as this?

Upon the horns of this beautifully counterbalanced conflict—dead against the living, hedonism against self-restraint, profaner against pardoner, sexuality against textuality—Ananthamurthy sets down an allegory of Indian history with a particular resonance for the 20th century, and indeed the one after. For although the novel appears to be set in the unchanging Village Time of old India, in actual calendar time we are somewhere in the 1950s, in the levelled world of the new Indian democracy, that has made its touchstone not the books of revelation, but a constitution thrashed out by human beings.

Slowly, our view of the dead man’s misdemeanours changes colour. Perhaps Naranappa, underneath the obvious provocation of his saturnalia, represents the spirit of the new freedom, blowing away the fossilised thinking sanctified by the centuries. In openly falling in love and living with a low-caste woman, Naranappa shows a greater humanity than that required merely by ‘keeping the faith.’ Unlike his compatriots, flapping cantankerously in manacles of jealousy and moralism, he thinks on his feet and with his body.

Even the spotless Praneshacharya finds himself morally discombobulated by the age: his righteousness is founded upon a deep social conservatism, and he thinks through the foundational categories of purity and pollution, which find no place in the new social compact. The brahmins, we see, are prisoners of history, huddled in a cocoon of hypocritical piety; never daring to live beyond the ‘duties a brahmin is born to.’ Teaching all other castes to keep their own boundaries, they preside over a sterile society, when the age demands a new moral creativity. When they face a dilemma, they delve into their palm-leaf manuscripts, not into themselves. Praneshacharya begins to perceive this, but is powerless to act upon his intuition. Until his body does. On a trip deep into the forest to seek out an answer at the feet of a god, he encounters Naranappa’s voluptuous companion and ends up sleeping with her.

Now Praneshacharya, too, is a sinner, forced to confront his own repressed carnality. ‘I suddenly turned in the dark of the forest,’ he ruminates. Smarting with shame but rapt with a strange exhilaration, he takes to the road, both running away from himself and in search of himself. Ananthamurthy’s finespun prose, rendered in exquisite cadences by his late translator AK Ramanujan, tracks with great rigor the inner monologue of Praneshacharya as he arrives a new vision of the self. And as we follow Praneshacharya there, we see that we have reached a point not just metaphysical but metafictional. In place of the Sacred Books, perhaps it is the novel that contains the wisdom and the doubt that India needs for a new age in its history (which would make Ananthamurthy a kind of novelistic Naranappa). It’s a startling story, one as provocative for its time and place as those of Cervantes, Sterne and Diderot must have been in theirs.

As these examples show, the work of novels is not confined to mere representation of historical realities (although this is where they may start). Rather, a novel may be a creative intervention in history in its own right—an actual agent of history, passing on to the reader who passes through its narrative field both its diagnostic powers and visionary charge. Indeed, from Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay to UR Ananthamurthy, Bankimchandra Chatterjee to Kiran Nagarkar, Qurratulain Hyder to Salma, Phanishwarnath Renu to Amitav Ghosh, novelists have generated some of the most layered and sophisticated visions of Indian history produced in the last two centuries. Yet as a group they fall into no school or political camp—some of them possess a conservative rather than progressive sensibility. What unites them is their interpretative power and their ability to illuminate and complicate the particular historical crux they focus on.

It would appear that there is something inherent in the novel form—the persuasive power and freedom of a story when compared to a discursive argument; the prospect of linking the world of the self with that of the community and society; the freedom to rove in spaces of the past that we cannot access by means other than that of the imagination; the potential to think dialectically in exchanges between characters or switches in perspective between the narrator and the characters—that makes the space of the novel a particularly fertile ground for historical thinking.

And when they are themselves reinserted into the canvas of Indian history, it seems to me that the projects of the Indian novel and that of Indian democracy (both fairly new forms in Indian history) appear uncannily similar—and perhaps similarly unfinished. As Indian democracy has over the last seven decades sought to fashion a new social contract in a deeply hierarchical civilisation, so the great Indian novel has attempted not just to address but also to form a new kind of reader/citizen, alive to both the iniquities and the redemptive potential of Indian history.