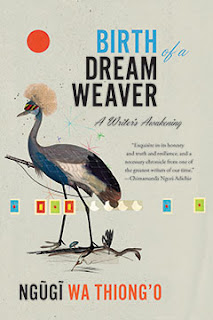

Have the pleasure and power that a BA in English can confer on a human being ever been described more movingly and inspiringly than in Ngugi Wa Thiong’o’s Birth of a Dream Weaver? The new book by the great Kenyan novelist and playwright, now 78 and a Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine, is the last of a trilogy of memoirs he has published this decade.

The story of his years at university, it can quite profitably be read on its own as the account of the ripening of a writer’s artistic consciousness. But for the full force of its revelations, ironies, and moral and literary cruxes, one should first take in its predecessors, Dreams In A Time of War (childhood) and In The House of the Interpreter (adolescence).

In those books, we saw the boy Ngugi growing up amongst a vast brood of siblings in the large, raucous rural homestead of his father, a goat-herder – and then suddenly being cast out when his mother, one of four wives, flees to her own father’s home after being beaten by her husband. We are in the nineteen-forties. The world is at war, and Kenya is an impoverished colony of Britain, with a nascent freedom struggle masterminded by an outlawed group called the Land and Freedom Movement, or the Mau Mau.

The young boy is poor, powerless and often hungry, the captive of a present “born of the power plays of the past”. He takes refuge from history in the consoling power of stories, including those narrated by a blind half-sister, Wabia. Although illiterate and a single parent, Ngugi’s peasant mother has many dreams for her son. When the boy wants to go to school, she makes a pact with him. She will find the money as long as he agrees “to always give his best”. This refrain echoes through the books, setting up the sense of a private ethic – the idea that one is answerable to oneself even more than one is to the world – that overrides worldly standards.

The young boy is poor, powerless and often hungry, the captive of a present “born of the power plays of the past”. He takes refuge from history in the consoling power of stories, including those narrated by a blind half-sister, Wabia. Although illiterate and a single parent, Ngugi’s peasant mother has many dreams for her son. When the boy wants to go to school, she makes a pact with him. She will find the money as long as he agrees “to always give his best”. This refrain echoes through the books, setting up the sense of a private ethic – the idea that one is answerable to oneself even more than one is to the world – that overrides worldly standards.

Having excelled at his studies, Ngugi wins a place at an elite boarding school, Alliance. He wears shoes for the first time and goes forth into the world. The ironies multiply: the arbitrary depredations of colonial rule menace Ngugi’s every dream, but it a school run by Christian missionaries that provides him a physical and intellectual sanctuary from the strife of the larger world. English books give him a sense of the power of literature and the imagination, but English is also the language in which the colonisers assert their power and stereotype the native as a primitive, not much better than a beast.

Now, in Birth of a Dream Weaver, the steadily expanding frames in the story of both mind and world reach an apotheosis. Innocence is no longer a virtue, or a crutch to hold on to. Ngugi is in his early twenties and has won a scholarship to Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, the most famous educational institution in East Africa. The sense of a divided self remains. The railways in Africa were set up for the exploitation of the continent’s natural wealth. Even in taking a train to Kampala, “I was benefiting from a history that had come to negate my history”.

But even so, Ngugi is now in a position to fight for his own side of history. Once a passive watcher of events in the world (“In my mind, political actors had always appeared as fictional characters”), he is now part of the intellectual elite of his generation. All around him, decolonization movements are changing the old world order; he looks up from his book to “the rise of new flags” and throws himself into passionate debates about race, religion, politics, language and literature.

Ngugi decides he wants to become a novelist, and is persuaded by his peers to become a playwright to dramatize the burning debates of the day. His work as an artist brings a new thrill and tension to the interplay in these books between the worlds, not always antithetical to one another, of “history” and “story”. When a contract for his first novel arrives in the post from a London publisher, Ngugi is over the moon.

Meanwhile, back in his native Kenya, the independence movement delivers the country back to its people. Ngugi leaves university both a free man – in the sense of having become an thinker who has transcended his limited origins – and the citizen of a free country. Even so, the book ends on an unusually pessimistic note, with dark forebodings of the crises to come: the dictatorship of Daniel arap Moi (under whose regime Ngugi would later be thrown into prison) and the sense that colonialism had, even in departing the scene physically, left its tentacles in Africa. The face of the young man slips away, replaced by that of a disappointed 78-year-old.

None of that will distract the reader, though, from the central emphases of these books: their unflinching faith in education and in the power of literature to liberate the imagination and ground the moral sense. Indeed, it’s hard to think of another living writer today – Orhan Pamuk, perhaps – who speaks so inspiringly and convincingly about the values of literature. For some years now, Ngugi has been spoken of as a likely candidate for the Nobel Prize. The publication of this riveting story of “how the herdsboy, child labourer and high school dreamer…became a weaver of dreams” makes this an ideal year to give Ngugi wa Thiong’o his due.

And some other old posts on the Middle Stage on autobiographies: "The acid thoughts of Sasthi Brata", "On Mahatma Gandhi's autobiography My Experiments With Truth", "On the memoirs of President Pervez Musharraf of Pakistan", and "On Muhammad Yunus's autobiography Banker to the Poor".

A slightly different version of this essay appeared in the Washington Post.