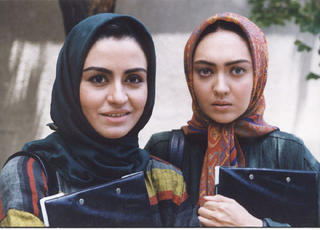

Briefly, Two Women is about the lives of Roya (Marila Zare'i, above left) and Fereshteh (Niki Karimi, right), two friends in the same class at university in Tehran. Fereshteh, who hails from the small town of Isfahan, is the more talented and accomplished of the two; what she wants most from life is to complete her studies and get a good job. But her life is suddenly threatened by a stalker, Hassan, who pursues her obsessively on his motorbike. He wants to marry her, but plucky Fereshteh laughs in his face and tells him to be off. He trails her as far back as Isfahan, where his pursuit of her leads to an ugly accident that takes the life of a child and lands him a long jail sentence.

That should be the end of Fereshteh’s troubles, but in fact it is only the beginning. Firstly, her father attacks her for having disgraced the family name, leaving her puzzled and angry. Then, a family friend, Ahmad, offers to pay the compensation the court has ordered Fereshteh to provide, and later he proposes marriage. Fereshteh finds herself betrothed to a man who is nominally a good husband, and later father, but who absolutely cannot comprehend the fact that she has some needs and desires of her own. Instead, suspicious of her ‘liberated’ ways (he arrives at this conclusion after he finds out that Fereshteh used to speak to male students while at university), he confines her to the four walls of their house. Confined to the duties of a wife and a mother, Fereshteh gradually loses all sense of herself and becomes a cipher, though she never stops fighting against her predicament. As Jasmin Darznik remarks in this piece: "A point of great irony and poignancy in the film is that Fereshteh acts as an acute observer of her own mental deterioration. She does not only suffer; she recognizes and articulates her experience with uncommon acuity."

In an interview Milani has argued that Two Women is “about the negation of the identity of a human being”:

One of the most important problems that we are faced with in Iran's society is that we are unable to express our true personality. Meaning that the society does not allow us to manifest who you really are, and this is worse in regards to women. In my opinion, 90 percent of the women and even the men in our society related to the character Fereshteh. The fact that in our society or in their private lives, there is a constant effort to change or make them into what they want them to be.The film’s last two scenes had every spectator in the theatre on the edge of their seats - here, Milani brings all the threads of the film together to achieve some kind of resolution, and the quality of her dialogue is exceptional.

First, fleeing from her home after yet another fight with her husband, Fereshteh runs into Hassan, now out of prison but even more embittered and vengeful than before. He chases her with a knife in hand, and corners her in an alley. Sure that she is going to die, she falls down on the ground and waits for him to knife her. The assailant and the victim whose paths first crossed thirteen years ago now encounter each other again. Both now look back at that time long past, and the refrain of the dialogue on both sides is ‘you didn’t let me’. “I would have done anything for you, but you didn’t let me!” charges Hassan. “I wanted to be everything for you, but you didn’t let me!” And Fereshteh, who has encountered far too much of men finding her culpable for their lives going off track, boils over in turn. Referring to how his pursuit of her changed her life forever, and threw her into a chain of events from which she could never extricate herself, she cries (I approximate from memory), “I wanted to study in peace, but you didn’t let me! I wanted to make something of my life, but you didn’t let me!” At this point Ahmad bursts in on the action, attacks Hassan, and is knifed by him while Fereshteh watches in horror.

And in the film’s last scene, we see Roya reunited with Fereshteh after many years, at a hospital in Tehran, where Ahmad lies critically ill. While Roya has retained her good looks, Fereshteh’s troubles have broken her spirit and given her a haggard, dejected appearance. The doctors tell Roya to prepare her friend for the worst. Roya takes Fereshteh home to meet her husband; there, they receive a phone call saying that Ahmad has died.

Fereshteh’s reaction recalls the famous soliloquies of Shakespeare’s tragic heroes: she wanders around the room voicing her thoughts to Roya and her husband, but in truth she is speaking to herself. “I loved him, as a prisoner loves his jailor,” she quavers. “I didn’t want him to die.” She struggles to grasp the implications of her new situation. “Roya!” “Yes, sweetheart?” responds Roya. “What shall I do now? How am I to take care of two children on my own?” says Fereshteh. And then something of the old, plucky, independent-minded Fereshteh returns. “I must learn a new skill to make ends meet – computers, perhaps. A lot of work lies ahead. I must start planning right away. There’s no time to be wasted.” As she goes on and on in this fashion it is clear – especially by the way she keeps saying “Roya!” - that she has to some extent lost her mental balance. Tears roll down Roya’s cheeks.

Milani says in her characteristically provocative manner:

The two female characters in my film are a single person with two personalities - the heroine's actual personality and her potential personality, what she is and what she wants to be but can't because of society and its mores.Clearly, Milani could not have made such a film without facing her own troubles with censorship. Indeed, the script of Two Women was thought to be so controversial that it took seven years for it to be passed by Iran’s Ministry of Culture, which monitors all film production in the country. After it was made, the film won several awards at film festivals around the world, and sealed Milani’s reputation. But, having tested the waters with Two Women, Milani got into even deeper trouble with the authorities with her next film, The Hidden Half, and was briefly jailed by the government. Milani speaks about the making of Two Women here, and gives an account of her own life and work here.

The story of Two Women has many parallels with aspects of the lives of women in India; among the Indian films I can think of which successfully explore the way women are imprisoned within gender roles is Shyam Benegal's Bhumika.

No comments:

Post a Comment