It would be hard for any reader now to keep up just with Indian novels, or books on Indian history, or Indian narrative non-fiction, let alone books from all these diverse fields. My list is no more than a small, very personal selection of the many high-quality new books published in India over the last two years.

To begin: novels. The two best Indian novels I read these past two years were Amitav Ghosh's River of Smoke, the second book of his ambitious and widescale Ibis trilogy, and Jhootha Sach, the Hindi writer Yashpal's massive magnum opus set on either side of the Partition years and in cities -- Lahore and Delhi -- either side of the border that Partition would make impermeable. Ghosh's protagonist in River of Smoke -- and the focaliser of much of the narration -- Bahram Mody, a character absent in The Sea of Poppies, is one of the most memorable characters in Indian fiction, and the Bombay and Canton settings of the book are exquisitely laid out even as the polyphonic narrative voices and linguistic play of The Sea of Poppies are carried over. I read the book over three days at a Portuguese deli in London, and they remain bright in my memory as three of the best reading days of my life.

Yashpal's novel, on the other hand, was first published in 1958; its size -- over a thousand pages -- perhaps prevented it from arriving earlier into Indian fiction in English. For its Tolstoyan sweep and density of detail, its realism with regard to human nature and its idealism about the power of human aspirations, and its magisterial overview of the religious cataclysms in the Indian subcontinent in the nineteen-forties, this novel seems to me a plausible contender for the greatest of all Indian novels. It is one of those books that one lives as much as reads. It is translated by Yashpal's son, Anand, and appeared in the Penguin Classics series -- to my mind the most diverse and exciting publishing list in all of Indian literature today. Longer pieces on Ghosh and Yashpal are here and here, and you should also read the translator Daisy Rockwell's essay on Jhootha Sach, "Night-Smudged Light". Among other Indian novels, UR Ananthamurthy's Bharathipura (Oxford University Press) deserves to be read by anybody interested in Indian fiction as an interrogation of the deep structures of Indian social life.

Yashpal's novel, on the other hand, was first published in 1958; its size -- over a thousand pages -- perhaps prevented it from arriving earlier into Indian fiction in English. For its Tolstoyan sweep and density of detail, its realism with regard to human nature and its idealism about the power of human aspirations, and its magisterial overview of the religious cataclysms in the Indian subcontinent in the nineteen-forties, this novel seems to me a plausible contender for the greatest of all Indian novels. It is one of those books that one lives as much as reads. It is translated by Yashpal's son, Anand, and appeared in the Penguin Classics series -- to my mind the most diverse and exciting publishing list in all of Indian literature today. Longer pieces on Ghosh and Yashpal are here and here, and you should also read the translator Daisy Rockwell's essay on Jhootha Sach, "Night-Smudged Light". Among other Indian novels, UR Ananthamurthy's Bharathipura (Oxford University Press) deserves to be read by anybody interested in Indian fiction as an interrogation of the deep structures of Indian social life.

In non-fiction, the two books by Indian writers that I enjoyed most couldn't have been written in more different styles, or had as their subject more disparate personalities: respectively a bar dancer in Bombay and an eighteenth-century Scottish natural philosopher. Sonia Faleiro's Beautiful Thing (Penguin/Grove), a book-length tracking of the rise, fall, and reinvention/suspension of Leela, a star of one of Bombay's dance bars, combined reportorial detachment and narrative empathy in just the right proportions. Faleiro's eye for detail is superior to almost any other Indian writer today, and her translations of Leela's talk into English initially appear patronising but only because they are so daring. Her work at the intersection of standard English and Indian English, or Indian English drawing on other languages, rivals the recent experiments in the same field by Ghosh and Vikram Chandra.

No human beings appear in the flesh in Kaushik Basu's Beyond The Invisible Hand: Groundwork for a New Economics (Princeton University Press and Penguin); there are only the intellectual ghosts of dead ones, particularly Adam Smith, whose ideas about the workings of markets and morality have been claimed and in many instances radically damaged by free-market thinkers of our time. But Basu has a wonderfully wry sense of humour, an eye for local examples for universal laws (such as the "ele bele phenomenon"), and an argumentative style so rigorous and yet unassuming -- consider the use of the word "groundwork" in his title -- that the three hundred or so pages of his book left me wanting much more. So I read it twice. The book is an elegant and unpartisan meditations on one of the great issues of our age: markets and their limits, and offers a roadway to rescuing free-market thinking from its more fanatical adherents. Chapter 1 of the book is here; you couldn't improve your brain more for an investment of Rs. 303. Basu's Twitter feed is consistently good reading too.

The scholar of religion Diana Eck's India: A Sacred Geography is a book that just can't be read without stopping -- only because so voluminous, rich, dense, and allusive -- and one which provides intellectual challenges and surprising connections from beginning to end. Its reading of Indian geography as a construct of the Hindu religious imagination before it was a secular cartographic map has a range that requires over five hundred pages to bring it out. “As arcane as lingas of light . . . and sacred rivers falling from heaven may seem to those who wish to get on with the real politics of today’s world,” Eck writes, “these very patterns of sanctification continue to anchor millions of people in the imagined landscape of their country.” a longer essay on her book is here.

I also found much to learn from about Bombay in Neera Adarkar's great anthology The Chawls of Mumbai: Galleries of Life (ImprintOne, longer essay here) and about the freedom struggle in Kashmir in Sanjay Kak's book Until My Freedom Has Come (longer essay here). Both these anthologies are primarily collections of essays by scholars and journalists, but neither Adarkar nor Kak are oblivious of the role of fiction in explaining the world and its dilemmas. The stories by the urban historian Prasad Shetty and the Kashmiri short-story writer Arif Ayaz Parrey are amongst the brightest lights in these books.

Short fiction. Anjum Hasan had already made a considerable reputation as a poet when she published her superb debut novel Lunatic In My Head in 2007, and last year she proved just as adept at the short-story form when she published her first collection, Difficult Pleasures (Penguin). Hasan brings a poet's startling perception and defamiliarizing eye to the observation of all her protagonists, as when the protagonist of "Banerjee and Banerjee", the economist Banerjee, is shown thinking -- entirely persuasively, if against the grain of the very story that is bringing him to life -- that "the crisscrossing of goods and services across the globe, created in hundreds of different environments and in response to countless human needs, is somehow a larger, better and more beautiful thing than any facts to do with individual lives."

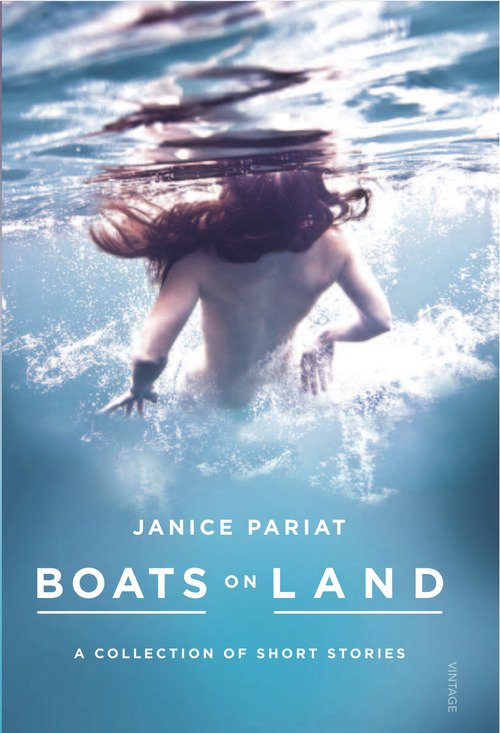

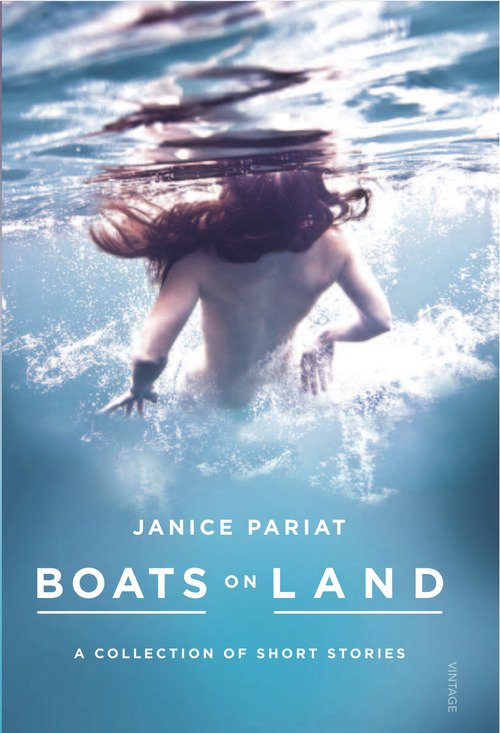

Another poet, Janice Pariat, established herself as a major new narrative voice -- lyrical, elliptical, and empathetic -- with Boats On Land (Random House India).

Another poet, Janice Pariat, established herself as a major new narrative voice -- lyrical, elliptical, and empathetic -- with Boats On Land (Random House India).

Gogu Shyamala's Father May Be An Elephant And Mother Only A Small Basket, But...(Navayana), rooted in the stories of Telangana in Andhra Pradesh and translated by several hands from the Telugu, impressed not only for the economy of Shyamala's style and the directness of the narration, but also because they take writing about Dalit protagonists beyond an older narrative binary of exploitation and suffering, enlarged and emaciated selfhood. Credit should also go to the publisher in working up a uniform and lucent English style for Shymala from translations by different hands.

Two works of fiction which had the words "Love Stories" in their titles were Annie Zaidi's Love Stories: #1 to 14 (HarperCollins) and Rajesh Parameswaran's debut collection I Am An Executioner: Love Stories (Knopf). Zaidi's work, taking one of fiction's most complex objects of inquiry head-on, was closely observed, multifaceted, and clearly thought through as a unity. "The One That Badly Wanted", about a girl who falls in love with a dead man, was a particular delight. Some of Parameswaran's stories indulged too heavily in the narrative hijinks that are a staple of the restless short fiction of our time, but his story about love in an alternative universe, “On the Banks of Table River (Planet Lucina, Andromeda Galaxy, AD 2319)”, was the most beautiful thing I read this year.

My poetic instincts are less sound than my prose ones and therefore my pursuit of new work in verse in India less secure, but over the last year I've dipped repeatedly into the bucking, slangy versions of Kabir produced by the poet Arvind Krishna Mehrotra in his ambitious Poems of Kabir (New York Review of Books/ Hachette) and the fourteenth-century Kashmiri mystic Lalded's exquisitely elliptical and jagged ruminations on life, god and human relationships rendered into English by Ranjit Hoskote in I, Lalded (Penguin). These are books that will speak to readers just as powerfully in a hundred years as they do now. Hoskote's magisterial introduction to Lalded is also the best single piece of critical writing to have come my way in the last two years.

Last: literary criticism and intellectual history. So much work in the West on the Indian novel focusses on the best Indian writers in English -- Rushdie, Ghosh, Naipaul, Seth -- that this bias seeps back into Indian literature and Indian bookshops. So it was great to see a completely convincing case being made for the Oriya novelist Fakir Mohan Senapati being not just a writer that Indians should read but one that readers around the world should read by the contributors of Colonialism, Modernity and Literature (Palgrave Macmillan/ Orient Longman), edited by Satya P. Mohanty, one of Senapati's translators. A conclave of Indian and American literary critics show that Senapati's riddling humour, circling and subversive point of view, and throughly original narrative technique make his novel Six Acres and a Third one of the greatest and most durable of Indian novels, one that, as the critic Himansu Mohapatra memorably writes, "reveals the causal joints of the world." All novelists desire to earn this compliment.

And finally, the intellectual historian DR Nagaraj, who passed away tragically early while still in his forties, left behind an astoundingly diverse body of work -- and a carefully sculpted point of view -- about Indian society, native traditions, Kannada epics and novels and literary criticism, communal violence, and the tension between Gandhian and Ambedkarite thought. Although sometimes prolix and orotund, Nagaraj's prose is also marked by fantastic metaphorical leaps and fine-grained reading of texts. The white heat of Listening to the Loom (Permanent Black), a posthumous collection of Nagaraj's essays put together by his student Prithvi Chandra Datta Shobhi, kept me up many nights in July. “If the methods and philosophical positions of present times are fit and useful to analyse the formulations of several kinds of pre-modern eras," writes Nagaraj, "the reverse should also be true.” His book is that pathway that runs back into the mists of time.

Happy reading in 2013!

To begin: novels. The two best Indian novels I read these past two years were Amitav Ghosh's River of Smoke, the second book of his ambitious and widescale Ibis trilogy, and Jhootha Sach, the Hindi writer Yashpal's massive magnum opus set on either side of the Partition years and in cities -- Lahore and Delhi -- either side of the border that Partition would make impermeable. Ghosh's protagonist in River of Smoke -- and the focaliser of much of the narration -- Bahram Mody, a character absent in The Sea of Poppies, is one of the most memorable characters in Indian fiction, and the Bombay and Canton settings of the book are exquisitely laid out even as the polyphonic narrative voices and linguistic play of The Sea of Poppies are carried over. I read the book over three days at a Portuguese deli in London, and they remain bright in my memory as three of the best reading days of my life.

Yashpal's novel, on the other hand, was first published in 1958; its size -- over a thousand pages -- perhaps prevented it from arriving earlier into Indian fiction in English. For its Tolstoyan sweep and density of detail, its realism with regard to human nature and its idealism about the power of human aspirations, and its magisterial overview of the religious cataclysms in the Indian subcontinent in the nineteen-forties, this novel seems to me a plausible contender for the greatest of all Indian novels. It is one of those books that one lives as much as reads. It is translated by Yashpal's son, Anand, and appeared in the Penguin Classics series -- to my mind the most diverse and exciting publishing list in all of Indian literature today. Longer pieces on Ghosh and Yashpal are here and here, and you should also read the translator Daisy Rockwell's essay on Jhootha Sach, "Night-Smudged Light". Among other Indian novels, UR Ananthamurthy's Bharathipura (Oxford University Press) deserves to be read by anybody interested in Indian fiction as an interrogation of the deep structures of Indian social life.

Yashpal's novel, on the other hand, was first published in 1958; its size -- over a thousand pages -- perhaps prevented it from arriving earlier into Indian fiction in English. For its Tolstoyan sweep and density of detail, its realism with regard to human nature and its idealism about the power of human aspirations, and its magisterial overview of the religious cataclysms in the Indian subcontinent in the nineteen-forties, this novel seems to me a plausible contender for the greatest of all Indian novels. It is one of those books that one lives as much as reads. It is translated by Yashpal's son, Anand, and appeared in the Penguin Classics series -- to my mind the most diverse and exciting publishing list in all of Indian literature today. Longer pieces on Ghosh and Yashpal are here and here, and you should also read the translator Daisy Rockwell's essay on Jhootha Sach, "Night-Smudged Light". Among other Indian novels, UR Ananthamurthy's Bharathipura (Oxford University Press) deserves to be read by anybody interested in Indian fiction as an interrogation of the deep structures of Indian social life.In non-fiction, the two books by Indian writers that I enjoyed most couldn't have been written in more different styles, or had as their subject more disparate personalities: respectively a bar dancer in Bombay and an eighteenth-century Scottish natural philosopher. Sonia Faleiro's Beautiful Thing (Penguin/Grove), a book-length tracking of the rise, fall, and reinvention/suspension of Leela, a star of one of Bombay's dance bars, combined reportorial detachment and narrative empathy in just the right proportions. Faleiro's eye for detail is superior to almost any other Indian writer today, and her translations of Leela's talk into English initially appear patronising but only because they are so daring. Her work at the intersection of standard English and Indian English, or Indian English drawing on other languages, rivals the recent experiments in the same field by Ghosh and Vikram Chandra.

No human beings appear in the flesh in Kaushik Basu's Beyond The Invisible Hand: Groundwork for a New Economics (Princeton University Press and Penguin); there are only the intellectual ghosts of dead ones, particularly Adam Smith, whose ideas about the workings of markets and morality have been claimed and in many instances radically damaged by free-market thinkers of our time. But Basu has a wonderfully wry sense of humour, an eye for local examples for universal laws (such as the "ele bele phenomenon"), and an argumentative style so rigorous and yet unassuming -- consider the use of the word "groundwork" in his title -- that the three hundred or so pages of his book left me wanting much more. So I read it twice. The book is an elegant and unpartisan meditations on one of the great issues of our age: markets and their limits, and offers a roadway to rescuing free-market thinking from its more fanatical adherents. Chapter 1 of the book is here; you couldn't improve your brain more for an investment of Rs. 303. Basu's Twitter feed is consistently good reading too.

The scholar of religion Diana Eck's India: A Sacred Geography is a book that just can't be read without stopping -- only because so voluminous, rich, dense, and allusive -- and one which provides intellectual challenges and surprising connections from beginning to end. Its reading of Indian geography as a construct of the Hindu religious imagination before it was a secular cartographic map has a range that requires over five hundred pages to bring it out. “As arcane as lingas of light . . . and sacred rivers falling from heaven may seem to those who wish to get on with the real politics of today’s world,” Eck writes, “these very patterns of sanctification continue to anchor millions of people in the imagined landscape of their country.” a longer essay on her book is here.

I also found much to learn from about Bombay in Neera Adarkar's great anthology The Chawls of Mumbai: Galleries of Life (ImprintOne, longer essay here) and about the freedom struggle in Kashmir in Sanjay Kak's book Until My Freedom Has Come (longer essay here). Both these anthologies are primarily collections of essays by scholars and journalists, but neither Adarkar nor Kak are oblivious of the role of fiction in explaining the world and its dilemmas. The stories by the urban historian Prasad Shetty and the Kashmiri short-story writer Arif Ayaz Parrey are amongst the brightest lights in these books.

Short fiction. Anjum Hasan had already made a considerable reputation as a poet when she published her superb debut novel Lunatic In My Head in 2007, and last year she proved just as adept at the short-story form when she published her first collection, Difficult Pleasures (Penguin). Hasan brings a poet's startling perception and defamiliarizing eye to the observation of all her protagonists, as when the protagonist of "Banerjee and Banerjee", the economist Banerjee, is shown thinking -- entirely persuasively, if against the grain of the very story that is bringing him to life -- that "the crisscrossing of goods and services across the globe, created in hundreds of different environments and in response to countless human needs, is somehow a larger, better and more beautiful thing than any facts to do with individual lives."

Another poet, Janice Pariat, established herself as a major new narrative voice -- lyrical, elliptical, and empathetic -- with Boats On Land (Random House India).

Another poet, Janice Pariat, established herself as a major new narrative voice -- lyrical, elliptical, and empathetic -- with Boats On Land (Random House India).Gogu Shyamala's Father May Be An Elephant And Mother Only A Small Basket, But...(Navayana), rooted in the stories of Telangana in Andhra Pradesh and translated by several hands from the Telugu, impressed not only for the economy of Shyamala's style and the directness of the narration, but also because they take writing about Dalit protagonists beyond an older narrative binary of exploitation and suffering, enlarged and emaciated selfhood. Credit should also go to the publisher in working up a uniform and lucent English style for Shymala from translations by different hands.

Two works of fiction which had the words "Love Stories" in their titles were Annie Zaidi's Love Stories: #1 to 14 (HarperCollins) and Rajesh Parameswaran's debut collection I Am An Executioner: Love Stories (Knopf). Zaidi's work, taking one of fiction's most complex objects of inquiry head-on, was closely observed, multifaceted, and clearly thought through as a unity. "The One That Badly Wanted", about a girl who falls in love with a dead man, was a particular delight. Some of Parameswaran's stories indulged too heavily in the narrative hijinks that are a staple of the restless short fiction of our time, but his story about love in an alternative universe, “On the Banks of Table River (Planet Lucina, Andromeda Galaxy, AD 2319)”, was the most beautiful thing I read this year.

My poetic instincts are less sound than my prose ones and therefore my pursuit of new work in verse in India less secure, but over the last year I've dipped repeatedly into the bucking, slangy versions of Kabir produced by the poet Arvind Krishna Mehrotra in his ambitious Poems of Kabir (New York Review of Books/ Hachette) and the fourteenth-century Kashmiri mystic Lalded's exquisitely elliptical and jagged ruminations on life, god and human relationships rendered into English by Ranjit Hoskote in I, Lalded (Penguin). These are books that will speak to readers just as powerfully in a hundred years as they do now. Hoskote's magisterial introduction to Lalded is also the best single piece of critical writing to have come my way in the last two years.

Last: literary criticism and intellectual history. So much work in the West on the Indian novel focusses on the best Indian writers in English -- Rushdie, Ghosh, Naipaul, Seth -- that this bias seeps back into Indian literature and Indian bookshops. So it was great to see a completely convincing case being made for the Oriya novelist Fakir Mohan Senapati being not just a writer that Indians should read but one that readers around the world should read by the contributors of Colonialism, Modernity and Literature (Palgrave Macmillan/ Orient Longman), edited by Satya P. Mohanty, one of Senapati's translators. A conclave of Indian and American literary critics show that Senapati's riddling humour, circling and subversive point of view, and throughly original narrative technique make his novel Six Acres and a Third one of the greatest and most durable of Indian novels, one that, as the critic Himansu Mohapatra memorably writes, "reveals the causal joints of the world." All novelists desire to earn this compliment.

And finally, the intellectual historian DR Nagaraj, who passed away tragically early while still in his forties, left behind an astoundingly diverse body of work -- and a carefully sculpted point of view -- about Indian society, native traditions, Kannada epics and novels and literary criticism, communal violence, and the tension between Gandhian and Ambedkarite thought. Although sometimes prolix and orotund, Nagaraj's prose is also marked by fantastic metaphorical leaps and fine-grained reading of texts. The white heat of Listening to the Loom (Permanent Black), a posthumous collection of Nagaraj's essays put together by his student Prithvi Chandra Datta Shobhi, kept me up many nights in July. “If the methods and philosophical positions of present times are fit and useful to analyse the formulations of several kinds of pre-modern eras," writes Nagaraj, "the reverse should also be true.” His book is that pathway that runs back into the mists of time.

Happy reading in 2013!